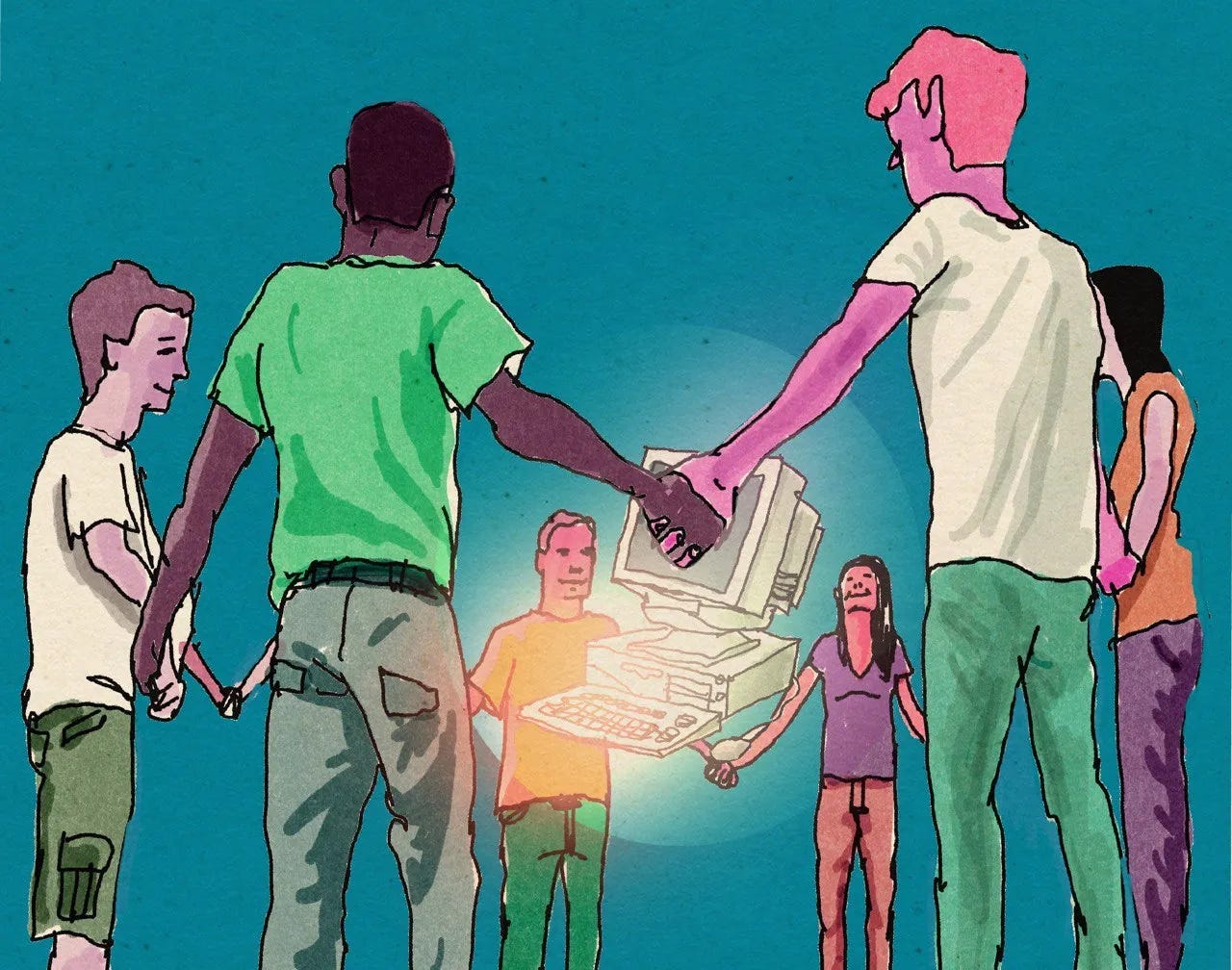

Self-adoption and the communal computer

The Machine has adopted you whether you know it or not. It's time to adopt yourself back.

I’m just old enough to remember when the only computer in my home was in the “family room,” or the “computer room.” The time spent on it was limited in two ways: there initially wasn’t as much to do on it back then, and the fact of it being a shared machine meant that the time spent on it had to be… shared.

Back then, the internet was less an abstraction connecting everything and more of an experience—so distinct from the world of flesh and embodiment in which most of our time was spent. It was separate, something that you knew you were entering into the moment you sat down at that communal computer, and that you could leave behind the moment you stood up and walked away. You and it, the Machine and what it could do, were felt to be separate. It was such a distinct thing that it even had a voice. This was a time when email was still a novelty, and the web pages that all seemed to have been designed in MS Paint loaded slowly from top to bottom. It was easy to remember you were having interaction with the Machine because of the sort of technological friction making it apparent.

At the time of writing this, I was 27 years old. I was born in 1994. I don’t know how adulthood or dating looked when the landline was among the sole lifelines between the distant, to say nothing of the days of the telegraph or letters. I can know so much more about so many things than many of my ancestors, many of whom were among the most educated of their eras holding positions as professors or doctors. I have unbelievable—previously inconceivable—access to near-instantaneous communication with innumerable people. I can be what’s almost a fly on the wall in conversations between impressive people in a few clicks of a mouse, listening to podcasts or interviews whenever I please. I can have anything I want, so long as it’s sold online and I have the funds. But this all seems to come at a Faustian cost, where atomization and distraction are nearly obligate concomitants of our collective conjoining with each of our personal Machines.

This communal computer came coupled with a sort of leash, an inherent domesticating feature, being in a shared space:

Your time spent on the communal Machine would be more or less measured by you or anyone else paying attention, thus you couldn’t just waste the whole day there. If you were avoiding chores, homework, or spending time with friends, it would be evident and located in a place.

If that curiosity about sex comes up (as is natural for young people and the bored or lonesome), the impulse to look to the Machine for answers might arise. But that impulse would be met with the knowledge that your search for “answers” could be interrupted by someone else with whom the communal Machine was shared.

Contrast this with today, where we all have constant access to the hardly recognizable entity that the Internet has become, capital-I, monolithic and all-pervading. You can hardly exist in our world without access to this monolith, and if you manage it for some reason or another, you’re at a severe disadvantage.

And that means that the time spent with the Machine is now an inextricable part of the fabric of daily life. More often than not, in-person contact with anyone you don’t work or live with is preceded by contact through your phone. At this point, we’re entirely used to the ability to communicate with basically everyone we’ve ever known. Be that a business connection met at a conference or a party, or every single person you’ve ever had a romantic relationship with, there are few barriers to reaching out. Instead of leafing through a dusty yearbook and reminiscing, you’re now empowered to see the most up-to-date curated version of anyone so inspired to broadcast their lives online. In place of capture, preservation, and reminder by memory and scant photographic or memorabiliac reminders, we now see the ghosts of our past made once again “real” and absurd by highlight reeling or verbal brain-dumping facilitated by social media.

As a result, these ghosts of our past are imbued with so much more potentiality: to contact, to reignite fondness more circuitously, or to see what hallways of life they now haunt and with whom they haunt them. And it’s all sanctioned by whim; few things save for your internal naughtiness bells ringing will stop you from “creeping” on a profile or sliding into someone’s DMs. Nowadays, there’s little risk your mother or brother or sister or father will stumble into your living space and see you as they might have walked into the family room in the days of the communal computer and AOL instant messenger. The Machine and you have become one, and those ghosts of the past are carried with you in your pocket instead of merely your memory.

This is all inclusive, too, of the sexually explicit material that has pervaded every nook and cranny of the web. It’s not a massive leap to say that the average porn viewer now has seen more bare butts and their associated pudenda than all of his recent ancestors combined, nudists aside. What’s worrisome is that the average age kids are seeing porn is 11 years old. There are few stops on this now that kids are given phones at a young age, often without any restrictions on their exploration of these same nooks and crannies. As these young ones, too many of whom were given tablets as a means of mollification, begin to self-mollify with whatever material they learn brings peace to the mind and relaxation to the body, the rates of addiction to porn will likely further climb. Their Machine is no longer out in the open, kept in the private-openness of a shared family room. It’s out of the way, easily navigable and its search history clearable; it’s in the pockets of all their friends, and it’s in their beds at night. But it’s not just a matter of concern for the younguns. With correlations with heightened divorce rates and lower satisfaction with one’s own sex life, the downstream effects of integrating your sex into the Machine aren’t without consequences. The piecemeal co-opting of your motivational system won’t be stopped by a stern talking-to from dad discovering your browser history.

You are free to indulge in this unprecedented escapism whenever a momentary urge arises, and nobody but the superego will be walking into the proverbial family room of the modern Machine-integrated person. We’re left to our own devices (literally) and our worst impulses are left unchecked by external circumstances, as they once had been to a greater degree. It’s up to the Machine-integrated individual to put a stop to whatever behavior it is, and each of us is himself embedded in a culture of other Machine-individuals. Our shared culture is increasingly onanistic and fascinated by being able to populate one’s own bedroom with the ghosts of days past. Confirmation bias paired with the pursuit of easy pleasures—and that ever-present resistance to give the warmth of easy enjoyment up—is pushing our shared boundaries further and further from where they were when we built the edifice within which we all exist.

Removing the Machine from oneself (or is it removing oneself from the Machine?) now feels as impossible as a human flight once seemed. But the Kitty Hawk flew and the Wrights rejoiced. Unplugging won’t be as dramatic, and might look like leaving your phone in a different room while it charges at night, or setting restrictions on the amount or kind of content you let yourself access. Unplugging might be pushed along by things as amorphous as “checking your intentions” before following someone or looking something (naughty) up, or “taking a moment” to see if you’re “doing what’s best” for your future self. You have to take on the job of self-adopting, becoming your own father: the one who might walk into the family room at any minute and catch you in the act—whatever the act might be. This all matters because, if we let it, the borderlines of our norms and mores we abide by will be slowly pushed away by the inchworming of easy pleasures, nostalgia-driven ghosthunting, and a culture built by coomers.