The ‘disease’ of addiction, an analogy

Addiction isn’t a disease. Addiction is merely *like* a disease.

Addiction is the spectre of our time. We all see its casualties haunt our streets while the market of attention tries to make addicts of us all.

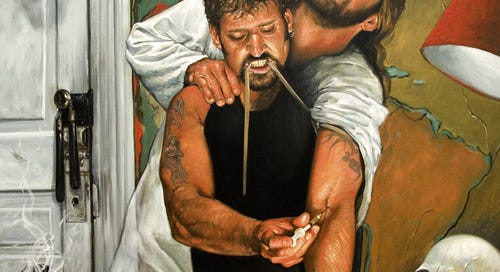

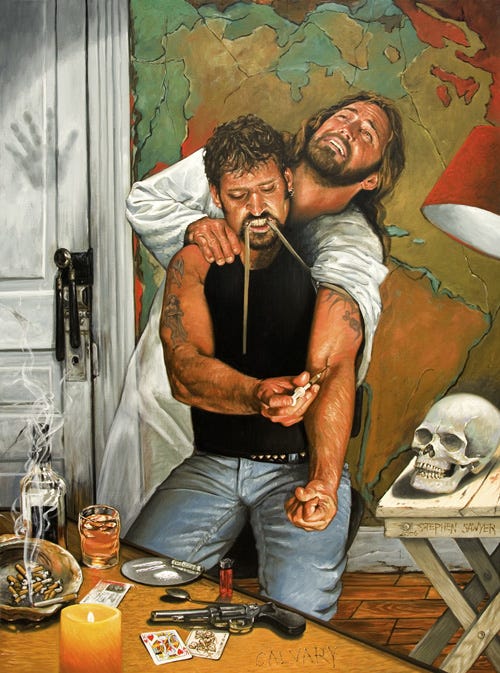

High, or trying to be (nowadays on P2P meth or synthetic opioids), the addict1 has lost something fundamental. For the addict, the fullness and range of human being is traded for what can fit inside a syringe, through a pipe, the neck of a bottle, or be horked through a nostril.

For the educated, progressive class, to say “addiction is a disease” is like saying “water is wet.” It has become a banal platitude, absent of real meaning. It’s easily stated but more often than not only half-believed. But addiction isn’t a disease. Addiction is like a disease. And it’s not like most diseases.

What addiction is most like is type 2 diabetes. Diabetics and addicts both experience dysregulation of innate, necessary systems. Both begin with volitional, normal actions that then mix up with features of an individual that were once categorized as merely moral failings, but now are parsed out into being things like genetic predispositions (e.g., ‘thrifty genotypes’), histories of adverse experience with food or early life stress (e.g., food scarcity or trauma), or socioeconomic situations (both drug abuse and type 2 diabetes show correlations with SES).

In the case of diabetes, without substrate for cellular respiration we die; and for the addict, without motivational systems pressing us to fulfill our needs, we die.

For the development of diabetes, the process basically works like this:

Your cells need fuel. Carbs are that fuel by default. So you eat something carby and now you have sugars in your blood. Most of your cells can’t bring that in without insulin, which acts like a key on the “glucose door” of your cells, allowing glucose in to be used to create usable energy. However, in the case of insulin resistance – something that can occur from constantly elevated sugar levels in the blood – cells stop responding to normal levels of insulin. In response, the pancreas (the organ that makes insulin) makes more insulin. And the cycle continues; more insulin leads to more insulin resistance, and more glucose builds up in the blood. Rinse, repeat. Eventually, this process leads to high levels of triglycerides in the blood, which is an indicator of insulin resistance, and has a slew of health effects described with the nondescript name “Metabolic Syndrome,” inclusive of stroke, heart attack, and type 2 diabetes.

Addiction functions in a similar way. Inclusive of your body’s need for food – hijacked in the process above – your motivational system cries out for regulation of its needs. If type 2 diabetes is a disease of energy regulation, addiction is a disease of emotion regulation.

To break this down, it begins simply, in an experience that many of us have in adolescence: a friend suggests trying something new; the would-be addict obliges and partakes. It’s normal to seek out novel experiences. It’s how we got where we are; it’s the same principle that made it so that you were born, led to the creation of the wheel, and allowed us to breach the firmament to land on the moon. Et cetera, so on, and so forth. What’s experimenting with drugs if not an extension of that process? It’s extremely normal. (Similar to how it’s normal to eat something sweet every now and again; and even drug-use initiation has a genetic component).

In some, this novelty drive ‘sticks’ to drugs of abuse. It’s common that something immediately clicks in the addict that doesn’t in the non-addict. The first hit of smack might alleviate some deep-seated anxieties; that first line of tweak might imbue some previously untouchable confidence; the first shot of liquor might do both at the same time. Regardless, it’s like a lock into a key.

The addict learns the emotional power of the actions associated with drug use. Similar to how a toddler learns that some foods fill the belly better than others, the addict learns that something tickles the proverbial giblets unlike anything else. Some people just hate the feeling of alcohol – it makes them dizzy. Others can’t stand opioids like codeine – it makes them itchy and nauseated. Others try either and fall immediately in love.

This is the crux of it: the process fundamental to developing an addiction isn’t some vile moral maladjustment. It starts as a process more similar to discovering a favorite food than immediately trading your grandmother’s soul for a baggie of powder after coming down from that first high. Why do we like some things and not others? Kick the can of causation back to before you were born: is it your mother’s doing? What about her mother’s then? If you don’t think about it too much, it’s like a really bad form of intuitive eating, where the hunger cues are more on the scale of a Kaonashi (No-Face) than your garden-variety granola eater. And instead of granola it’s scheduled narcotics.

Ultimately, for the addict that something new becomes just another well-mapped part of the motivational territory. To assuage some boredom or take it easy after work, you might opt for Netflix or empty-minded scrolling on the web. The addict’s setpoint gets pushed a bit differently. Netflix alone won’t do. Because of neuroadaptive processes, biologically not dissimilar to the desensitization to insulin’s activity in the case of diabetes, the titillation centers of the brain become less responsive to naturalistic rewards.

Eventually, the thought of buying a baggie of H appears as readily as deliberating whether one wants to go on a run or watch Succession. In the earlier stages, these thoughts might co-occur. (I had a good friend who said that early on in using heroin he stubbed his toe and thought Well, I know something that’ll make that feel better.) And eventually, that something wins. The days when the dosing becomes more frequent, it takes over. It’s like overloading glucose in the blood of pre-diabetic. The body fights to maintain balance: with so many feel-good chemicals bursting into one’s blood, the body ramps down its own endogenous feel-good chemicals. Repeat the cycle of dosing-withdrawal enough, you have a problem. The body’s ability to self-regulate its drive toward assuaging need states goes off the rails because an artificial, supernormal need state has been inserted into the mix. Due to processes involving epigenetic priming in concert with circuit-level “cells that fire together wire together”-ing, drug-induced dysregulation of executive function, genetic predispositions, allostatic load, and just good old fashioned knowing what you’re missing out on, and you have a set of very real biopsychosocial consequences that pretty significantly take agency – that necessary feature of moral culpability – out of the equation. It begins with knowing volitionality and ends with a process that feels as natural as seeking shade from the sun or warming up by a fire on a cold night.

The addict’s brain becomes, for lack of a better word, addled. This is a biological process, involving the same sorts of biological mechanisms as those involved in type 2 diabetes but in a different organ.

A note: I use the term "addict" to describe individuals suffering from substance use disorder. I do this for two reasons. The first is because that is what many call themselves; in the context of The Rooms of AA (& its related sub-fellowship offshoots), the introduction of those in attendance is "My name is John, addict/alcoholic." The second is because alternative renderings are cumbersome and, frankly, stylistically unappealing.